Kaushik Subramanian’s VC Learnings After 2 Years

Posted by @TheHolyKau on April 3, 2025, at 12:05 UTC

I completed 2 years in VC last month. I’ve led a few deals, seen some uprounds, and navigated crises. I’ve also lost a bunch of deals. Here’s what I learned, written as notes to myself, some where I did a 180 on what I thought before I started:

1/

Sales: VC is a sales job and a sales job only. Our job on the investment side of things is to a) get access, b) get information and c) decide whether to invest. VCs will do anything for a and b - creating theses, intros, market maps, hosting dinners, reverse somersaults etc. However, only a few VCs end up in a position to run through the info, decide not to invest, and STILL leave with positive NPS. This is the craft!

2/

Uprounds: Getting up rounds done is HARD, especially if not AI or flavour of the season. Founders will fall prey to VCs doing a) and b) above, think there’s a lot of interest in the company, and not do the dance. Or worse, start ‘picking’ on interest rather than offers, and limit top of the funnel. Being a founder is lonely af with no feedback, so founders mistake VC interest as interest to invest when it is interest to ‘know more’. The moment VCs know more, founders lose all leverage.

3/

Losing: Damn, losing deals sucks. It’s the worst feeling. I lost a deal with an ex-colleague where I thought I had it ‘in the bag’, lost another because I sat by the sidelines too long, and lost another because of dilution concerns. Pay attention to losses that feel long-term bad. Those are the ones you truly believe in.

4/

Gut: Trust your gut. I’ve met ~600 founders so far (we count). If my gut feeling isn’t developed after meeting so many founders, I shouldn’t be doing this job.

5/

Brand dissonance: Some ‘great’ funds you see, read about, or listen to their partners on Acquired and 20VC are actually not great as a general rule. Some have had bad behaviour with founders, companies, or both. A great fund doesn’t necessarily mean great behaviour.

6/

Boards: Most boards suck and are ineffective. I will die on this hill. It’s hard to simultaneously a) have a high-quality board b) have them physically and mentally present for 3-5 hours a quarter and c) have a free-flowing, high signal conversation. The board concept probably makes sense for a cobwebby old school company, but not for fast growing early/growth stage tech companies. Founders would be better off with 2-3 directors who actually give a shit and a whiteboard. IN PERSON!

7/

Returns: It’s HARD to make big money (like actual $) in VC. You can either:

a) Invest at pre-seed, then invest in every round until C. You’re ‘flat-ish’ MOIC wise until Series C AND you are making the same investment decision everytime with negative NPS almost guaranteed if you say no. See below as a typical illustrative example:

- 2M on 10M post pre seed, capital invested 2M

- 5M on 30M post seed: pro rata of ~1M

- 15 on 75 post Series A: pro rata of ~5M

- 40 on 250 post Series B: pro rata of ~10M

Total capital at work ~ 18M with a blended MOIC of ~2.75. You can run the math on this whichever way you want, but the meaningful uptick for capital at work only starts happening after this point

b) Wait until the A, and then assume that you will win it. Unless you’re already a heavy hitter, the best way to do this is to pre-empt. This means you will do this on incomplete/limited information, no data room (hey, I’m not raising, the founder says), and limited touch points with the founder. So you’re putting in a 15M-20M check at 75 post with v v high risk. Next round Series B, 40M on 250M with a contribution of 10M you end up with similar MOIC as above

You are either taking multiple decisions or bundling up the risk in one high-stakes decision with a similar MOIC that you will report to your LPs. That’s hard!

8/

Frenemies: Everyone is your friend until you are in contention for the same deal.

9/

Ownership: ‘We increase ownership in our winners’ sounds great mathematically but is nearly impossible to do practically. If a company is a winner, the next investor will push everyone else out, and it is nearly impossible to get super pro rata by the time you know the company is already a winner. Before it is a winner, well, why would you increase ownership? Better to get in with the ownership you want.

10/

Smarts: Just because someone’s invested in multiple winners doesn’t mean they’re smarter. Many VCs have a hindsight thesis and get a lot of shit wrong.

11/

Shots on goal: More shots on goal IS important. Being selective is good (you have to be), but knowing when to stop analyzing and pull the trigger is important. The more investments you make, the more exponentially likely you are to find winners versus linearly.

12/

Network: Network is EVERYTHING. A differentiated network leads to differentiated sourcing. Differentiated sourcing means you see deals before others, so you don’t have to worry about winning as much.

13/

References: References on the founder are more important than the rest of the due diligence put together. Talk to more of the founders past associates than you spend time thinking about TAM. People rarely change behaviours, and more than one instance of bad behaviour is a habit. One founder I almost invested in referenced badly when I dug deep, and thank god I spent time doing that.

14/

Winning: You can win on a) speed b) price c) brand d) personal reputation. There will always be someone better on c) and d), and different venture funds play different games, so b) is not a reliable strategy for me. It’s always better to be fast, as fast as possible.

15/

Games: Different venture funds play different games, so some deals don’t ‘make sense’. Some venture funds are looking to return 3x, others are happy even with a 1x, some are playing a completely different strategy and several do venture just as an experiment.

16/

Negotiation: Don’t negotiate against yourself. Lowball offers usually lead to immediate rejection from founders, but also know where to draw the line on overpaying. For a first offer, expensive is fine, but ridiculous is not!

17/

Conviction: Conviction cannot be price dependent. A great company is a great company, irrespective of price. This is for a true venture outcome. Read this in conjunction with the earlier point.

18/

Pricing is just what someone is willing to pay. So don’t look for logic in the other person’s price as long as you have your own logic for yours.

19/

Don’t second guess yourself. If the founder says they will move mountains, they will move mountains. If the founder says they will make cars fly, they will make cars fly. If you fundamentally don’t believe that, then you lack conviction. I wanted to pull the trigger on a deal where I kept second guessing a bunch of ridiculous things the founder said he’d do - and guess what - he did most of them.

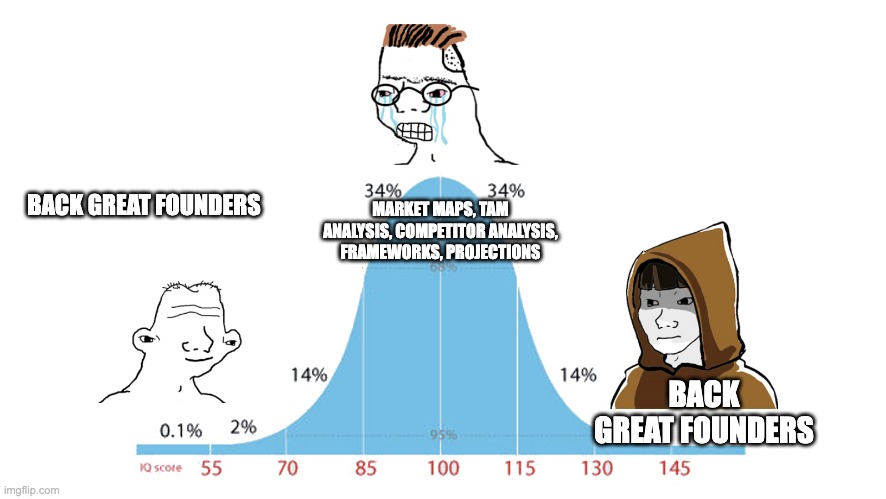

(a graph about IQ and backing great founders)

20/

The only truth in VC: Image Link

21/

More long form here along with earlier years learnings: substack